Past Prime Issue #17

Billy Joel, Phish, Rush, Pitchfork & Joe Niekro

Not to get too personal here, but a few weeks ago something happened. While watching The Grammy Awards — which I only agreed to as an act of solidarity with my Taylor & Olivia-loving daughter — I started to feel really sad. You see, after weeks of promotional teasing & hours of Trevor Noah’s prodding, Billy Joel — awkward, stiff & leaky-eyed — got on stage & performed his first new song in decades. I haven’t been the same ever since.

In New York’s Bridge (New Jersey) & Tunnel (Long Island) Civil War, Bruce was Union & Billy was Confederate. Two inordinately gifted men, born a hundred miles apart, but separated by galaxies. Bruce worked so hard while Billy tried so hard. This was canon. I had retold myself this story for most of my life. But, forty years after I decided that Billy was not my guy, I felt a twinge. There he was — an old, sad (gran)dad, who’d given up on Pop music because — despite his massive popularity — all he could hear was rejection. At seventy-four, he looked older than his years & profoundly uncomfortable. He was no longer Billy The Kid. Not even really The Piano Man. But he sounded oddly wonderful. Moreover, according to my tween daughter, Olivia Rodrigo loves Billy Joel. And as the saying goes, a friend of my daughter’s para-social friend slash idol is also my friend. People — the war is over.

P.S. While I hope everyone reads every article in this edition, if you can only read one, please check out the piece on Bry Webb of Constantines. He deserves it.

Priming the past.

I have a Phish problem. Or at least, for the last thirty years I’ve told myself that I have a Phish problem. This problem is in spite of my complete adoration for the state of Vermont. In spite of my having seen Phish perform live multiple times. In spite of being occasionally, but earnestly, wowed by the wizardry of their jams. In spite of my appreciation for their business acumen. In spite of my loving their Ben & Jerry’s flavor. Yes — in spite of all of it — I don’t abide. Which, for most people, would not be such a problem. But, as a Vermonter at heart, I am left with this unrelenting pull between my YES-Vermont soul and my NO-Phish conscience. It is a battle that, until recently, I had ignored. But it was a battle that I knew — someday, somehow — I’d need to resolve. February 8, 2024 was that “someday.” “Fuego” was that “somehow.”

It’s been a couple of months since Condé Nast’s decision to reorganize & downsize Pitchfork, a move that drew head scratching disbelief & foot stomping ire from everyone with an opinion on the matter. As with all corporate shake-ups, the full implications won’t be understood for some time. But what is knowable now & for certain, is that (a) many people lost their jobs, (b) Pitchfork was one of the first Condé Nast titles to successfully unionize & (c) the writing at Pitchfork was never better than it had been recently under Editor & Chief, Puja Patel. Meanwhile, what should have been known to Anna Wintour (Condé Nast Chief Content Officer), Roger Lynch (Condé Nast CEO) & Nick Hotchkin (Condé Nast CFO), is that nobody under the age of fifty gives a shit about G.Q. (the title that Pitchfork was reorganized into) & that many people give many shits about Pitchfork.

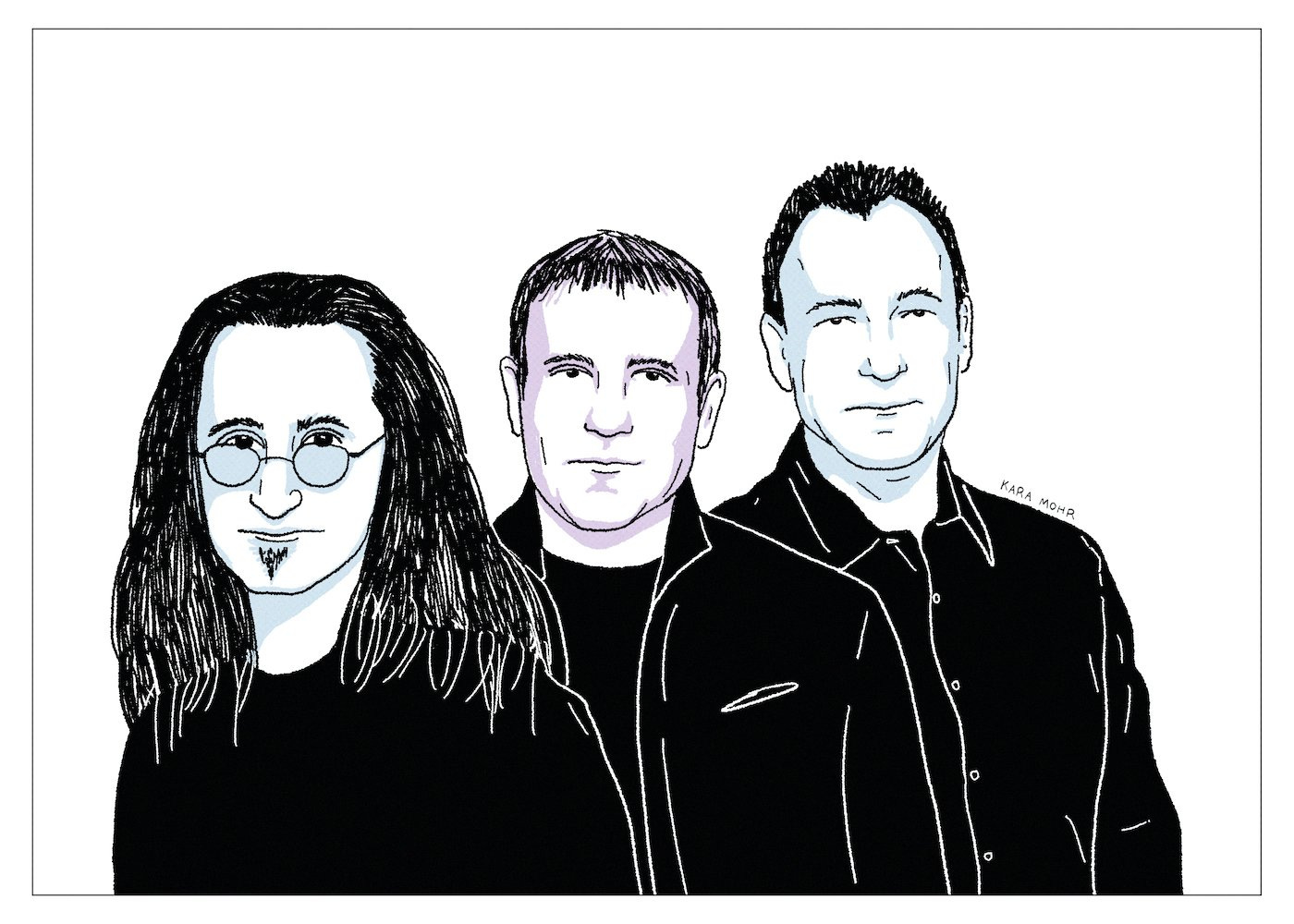

By the time I reached middle age, my longstanding, polite refusal of Rush had settled into a wizened indifference. In fact, since I was not a subscriber to Guitar World or Drummerworld magazines, many years would go by without me hearing a peep about the band I’d once tagged “Loser Van Halen.” But then, one day, I caught wind of “Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage,” a documentary that was generating buzz on the festival circuit. That buzz swelled, culminating in awards, which begot a short theatrical run, which is where, in the summer of 2010, I was confronted with the most unfathomable question: What if the band I liked the least was the one I loved the most?

Nada Surf, Superdrag, Fountains of Wayne, Harvey Danger, Semisonic. There is a cohort of Modern Rock bands from the Nineties who made off-kilter Power Pop & who became briefly, somewhat famous. But Fastball was different in that (a) they were more than just somewhat famous & (b) when they faded, they plummeted. Moreover, unlike their peers, Fastball was not retrospectively considered under-appreciated. In fact, they were hardly reconsidered at all. Fastball never had a second act as prestige artists on an Indie label. Never had a third act as songwriters to the stars. Buried under a pile of Gin Blossoms, they just — & just barely — kept going, writing great songs & making very good albums.

Some bands are corporations, like The Rolling Stones. Some are communes, like Big Thief. Some are gangs, like The Clash. The Constantines, however, were more like a union — the genuine article. They were brothers in arms — in jeans & flannel — and the greatest live club band of my lifetime. But when their mission inevitably bumped up against the realities of family & finance, the union dissolved. The miracle was not that The Cons broke up. The miracle was that they were so true & so committed for as long as they were. Just four albums. Not even a decade. But they never stopped waving the flag. Never stopped working. Which is why Bry Webb needed a break. Why, first, he left for Montreal. And then to Guelph, outside Toronto, where he started anew — as a husband, a college radio programmer & the maker of quiet, plaintive songs about the glow & glare of new fatherhood.

Past Prime pastime.

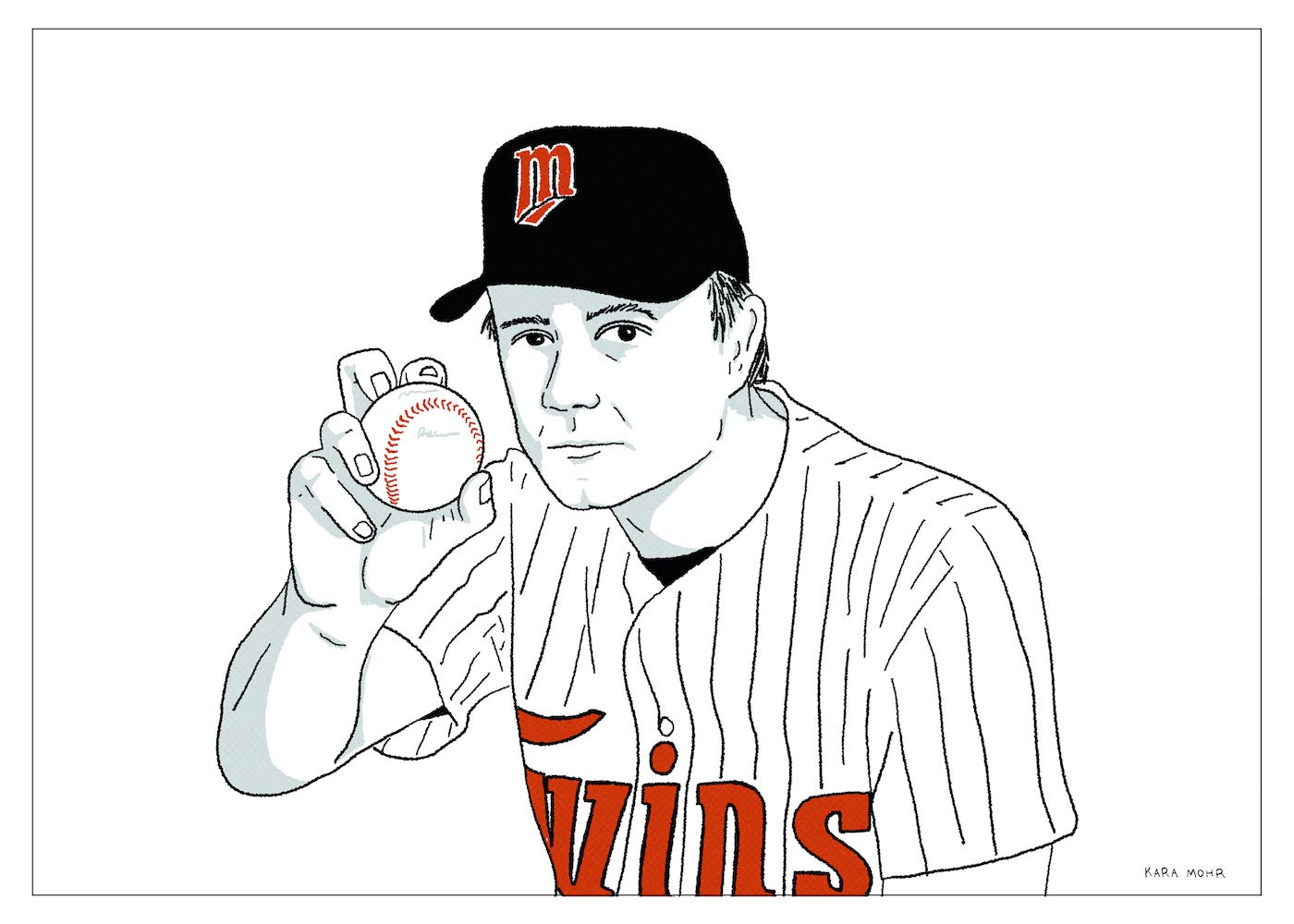

Joe Niekro “Do I Look Like a Doctor?”

For twenty plus seasons & with the possible exception of Gaylord Perry, no pitcher doctored more baseballs than Joe Niekro. Despite two decades of skirting the rules, though, Niekro was caught just once, in 1987 when he was tossed from a game by umpire Tim Tschida. Niekro’s ball mutilation was a long held, open secret that players, managers, umps & even fans were complicit in. But why? Why did we offer him such radical empathy? Perhaps because, in time, we all watch people around us become Joe Niekro. We ignore mild transgressions against nature in some sort of communal fight against aging. It’s only when it becomes too transgressive — when emery boards go flying or the third face lift becomes too difficult to look at — that we find our our collective, inner Tim Tschida & start moseying up to the mound.

Great articles. Glad you found me.