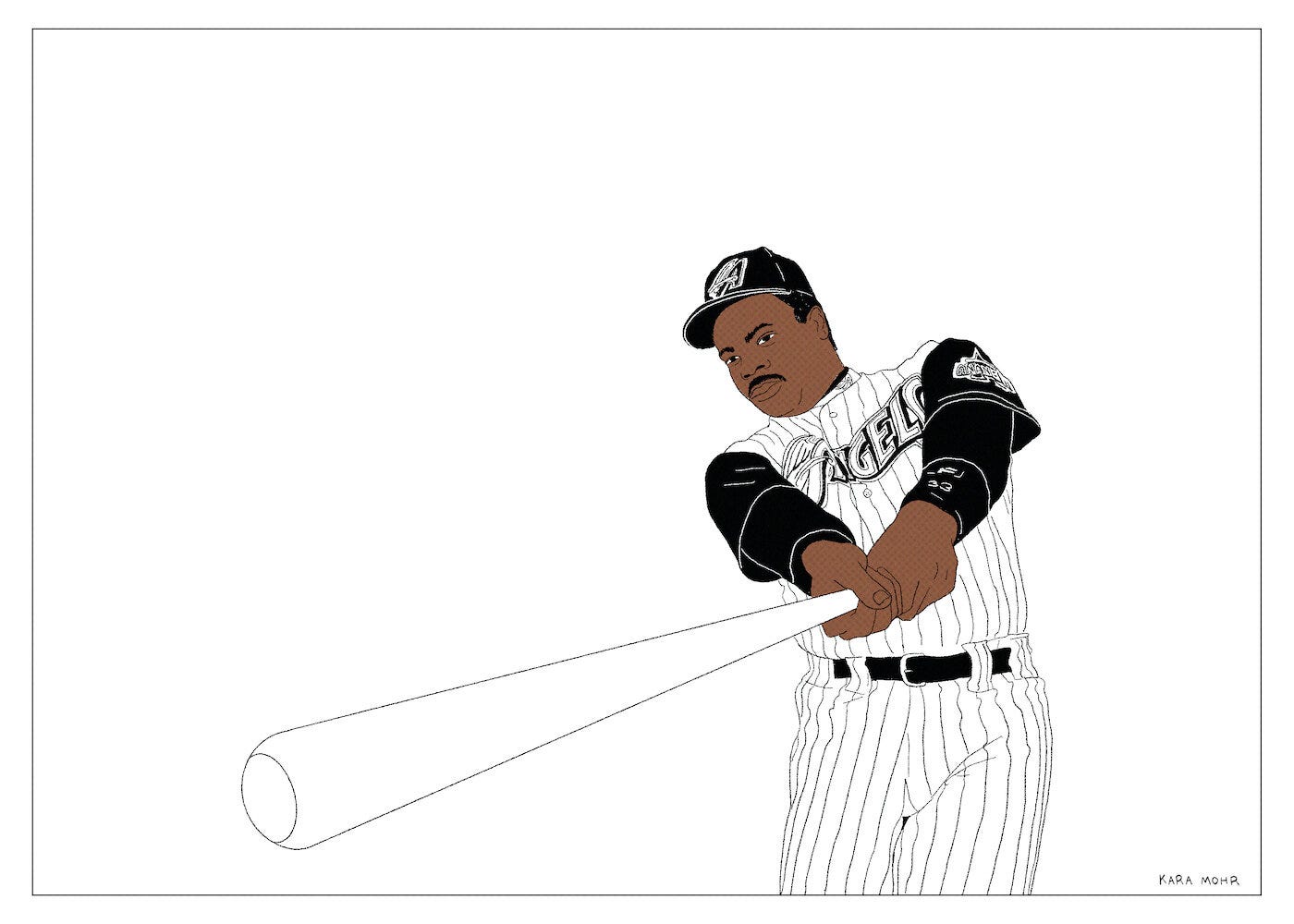

Somewhere just ahead of my daily walks to the mailbox to check for letters from our kiddos at summer camp (quick analysis: three children, five letters total, not awesome) but probably right behind our milestone birthday trip to Italy (quick review: very old, very beautiful, very cool & lots of smokers), the highlight of my summer was watching the entirety of an August, 1979 match-up between The Yankees & The Orioles. Though that game is famous for The Bombers emotional comeback win on the day of Thurman Munson’s funeral, I was rapt for a very different reason: to observe young Eddie Murray.

The grainy broadcast did not disappoint. Howard Cosell announced. Reggie Jackson repeatedly fell to one knee while swinging & missing. Lou Pinella wept. Ron Guidry got knocked around, but still threw a complete game. And Bobby Murcer was the hero. But I stayed up until 2am to watch Eddie Murray — my all time sports idol — drop a perfect bunt down the third base line in hopes of igniting a rally. It reminded me of two things that I always tell me kids: (1) “the little things do really matter” and (2) “you won’t remember the wins or losses, or the summer camp letters or that piazza in Rome — but you’ll always remember the night you wasted watching three hours of vintage baseball.”

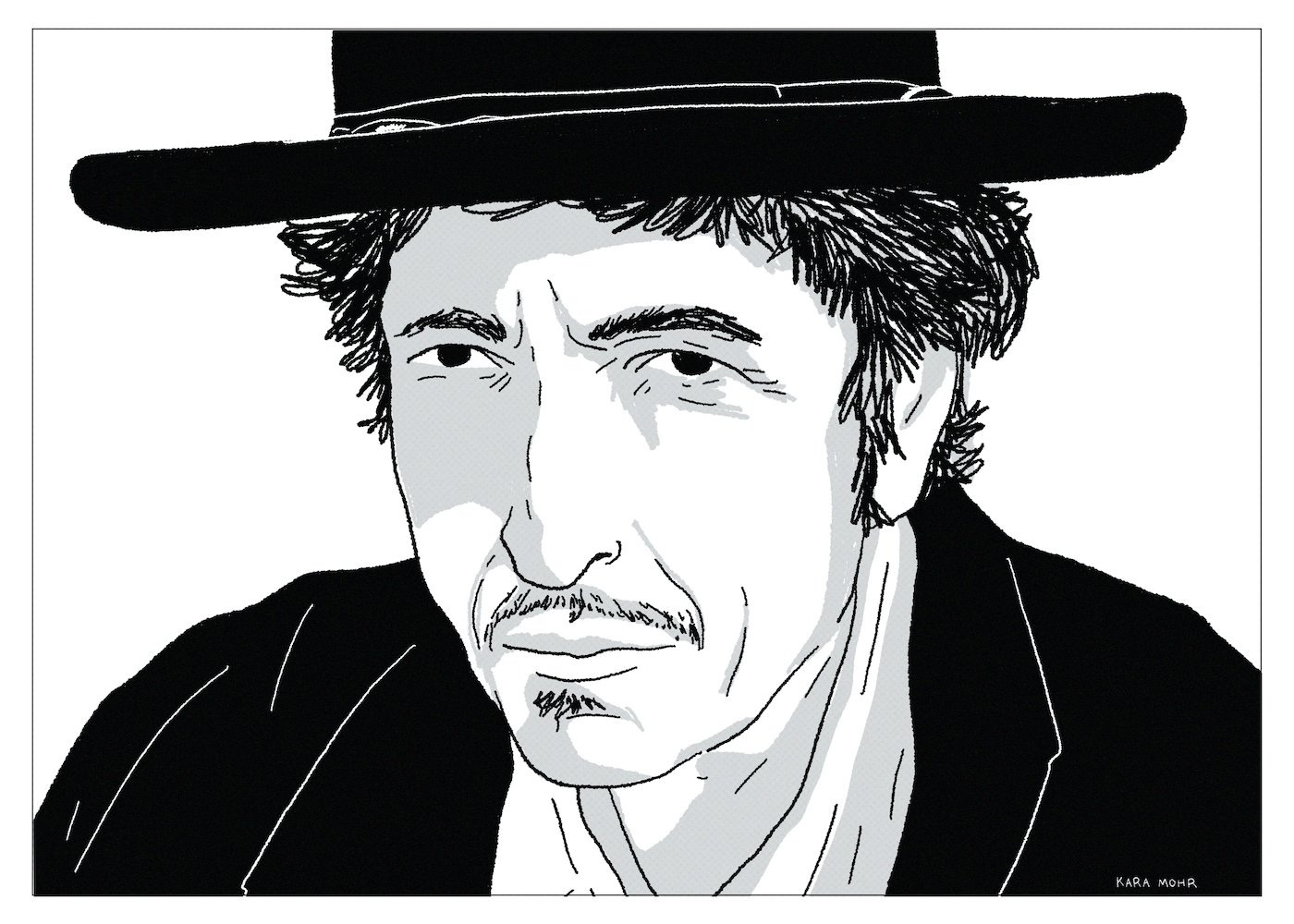

Bob Dylan “Together Through Life”

If Past Past Prime Van Morrison sounds like disgruntled Soul, and if Past Past Prime Leonard Cohen sounds like breathy Tao, Past Past Prime Dylan sounds more like Willie Nelson. It’s the sound of an artist working tirelessly, but with an air of retirement. The stakes are lower. There’s nothing to prove. And even if he had an agenda it would be swallowed up by his voice. That voice. The voice of relief and release. The voice of self-knowledge and self-acceptance. If you squint your ears, those post-”Time Out of Mind” records — from “Love and Theft” through “Tempest” — sort of blend together. The bands vary. Stories and settings change. But they share a common pace, range and — most of all — voice.

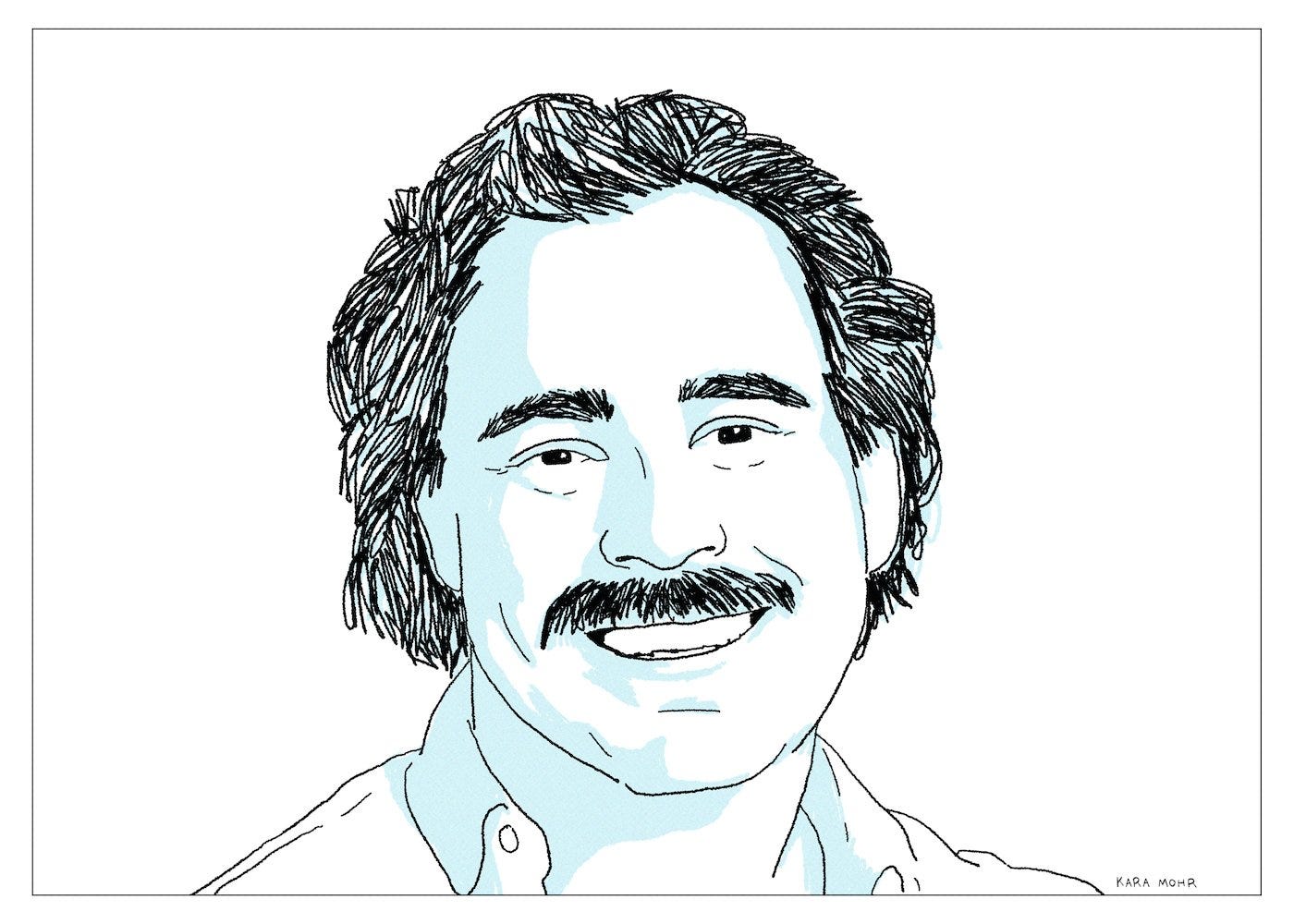

Buffett’s eighteenth studio album was both his first to reach the top five on the sales charts as well as his first Platinum-seller since the 1970s. Its title is a nod to fans — those sun loving, clothing optional weirdos who sometimes get drunk and say silly things but who possess a positively essential joie de vivre. It almost goes without saying that most Parrotheads are not clothing optional weirdos. But it’s also worth saying that many of the teachers, lawyers and middle-managers that comprise his fanbase do fantasize about being carefree, clothes-free beach dwellers. And that is precisely Buffett’s appeal — how he taps into a primal need to escape. An urge to — every once in a while — exist in a liminal space between feeling warm and feeling nothing at all.

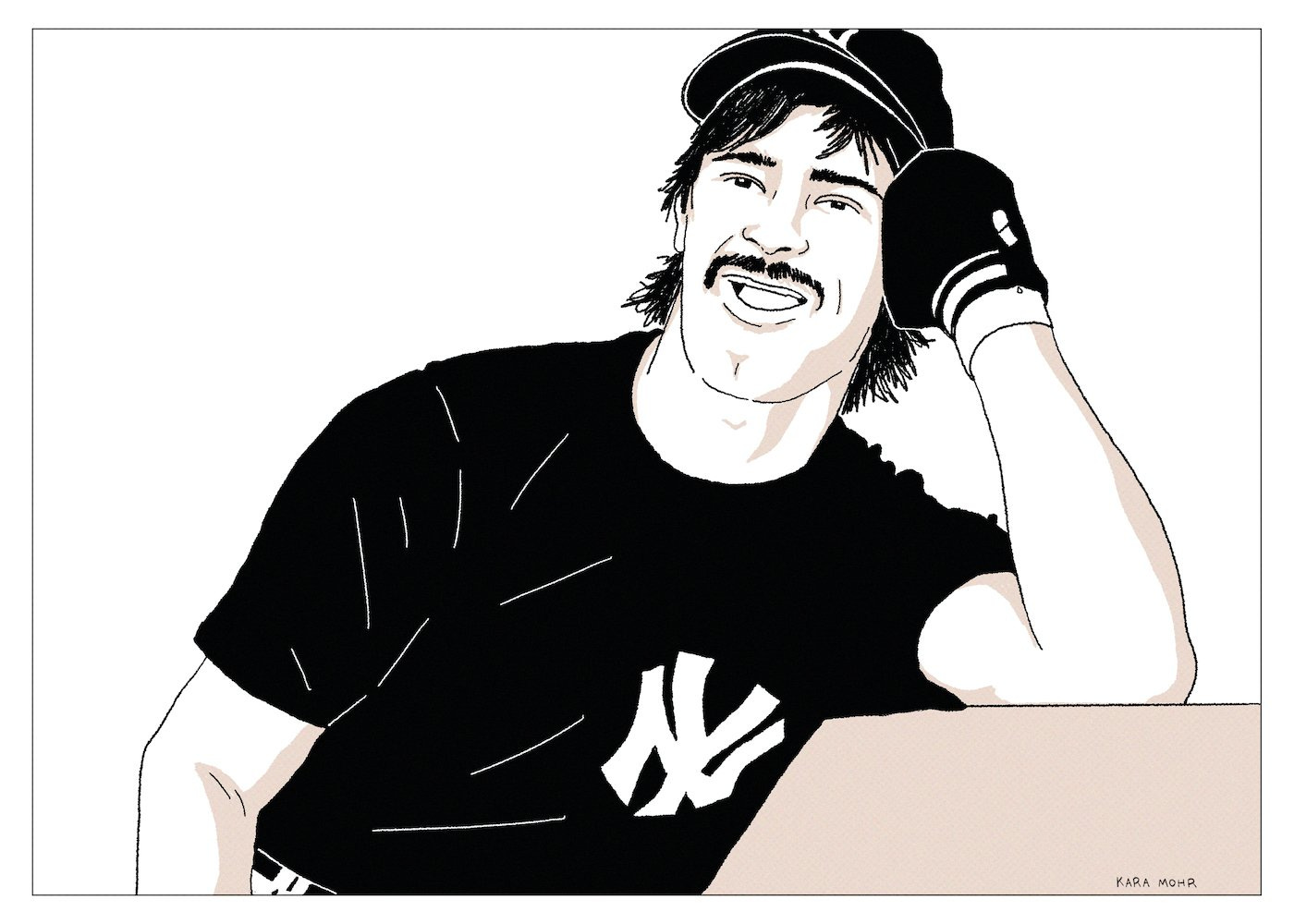

Don Mattingly “The American Dream”

By the time Don Mattingly became the Yankees’ captain in 1991, the franchise had already won twenty-two World Series championships. They’d not won one, though, during Mattingly’s career. In fact, they’d not even been to the Fall Classic. But during his final season in 1995 — a season in which he limped his way to seven home runs and forty-nine RBIs — the Bronx Bombers finally made it to the playoffs. According to the story of The American Dream, Donnie Baseball’s work ethic should have been validated by a championship ring before he was put out to pasture. And, true to form, he tried. The badly hobbled Mattingly — as one last testament to the power of will and determination — hit .417 for the series with six RBIs and a magical go-ahead home run in Game Two. But, in the end, the Yankees lost, Mattingly retired and returned to his horse farm in Evansville. The next year, without Mattingly, the Yankees would win the World Series. And then again three more times in the next four years.

Frampton’s appeal was something like Xanax — it was a mild but neutered sensation. He possessed a rare capacity to elicit pleasure without the charge of Rock and Roll. Which is not to discount his talent so much as it is to explain why he was so positively vital in 1976 and so completely antithetical by 1977 — the year in which “Rumors” and “Never Mind the Bollocks” exploded with feelings. Amazingly, 1976 was also the year that the U.S. patent was awarded for Alprazolam — known commonly as Xanax. Yes — Xanax arrived at precisely the same time that Peter Frampton dominated airwaves and record store shelves. However, it did not take long for the effects to wear off and for everyone — including no doubt Frampton himself — to realize that we needed to actually feel the feelings.

If Lou Reed was the first and the alpha, then Lou Barlow was the distant second and the beta Lo-Fi Lou. With Sebadoh, Barlow invented the kind of work in progress, kind of perfect as it is style that Guided by Voices and Olivia Tremor Control soon perfected. With Sentridoh, he invented an even quieter, decidedly unpunk alter ego that Iron & Wine and The Microphones cribbed notes from. And before all that, of course, was Dinosaur Jr., where Barlow’s Cardigan Cat Guy guise debuted. Yes — before Kurt Unplugged, before Elliott at The Oscars, and way before Taylor’s Tortured Poets Department — Lou Barlow was whispering the way.

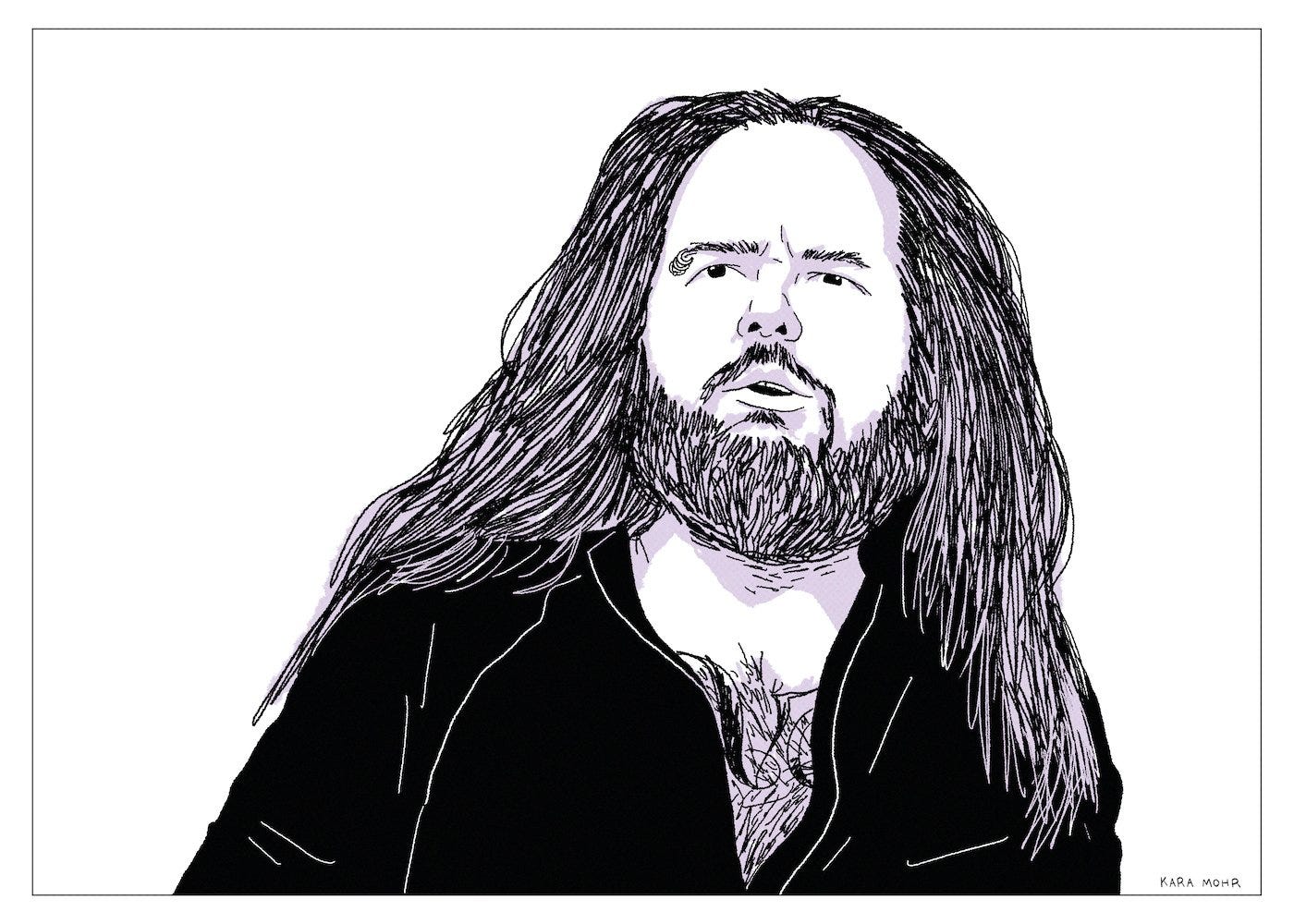

Jonathan Davis “Black Labyrinth”

The Jonathan Davis who released “Black Labyrinth” looked remarkably similar to the one who’d conquered the world on “Follow the Leader.” Same dreads. Same black glasses. Same eyebrow ring. Same scraggly beard. But in 2018 the almost forty-seven year old was an elder statesman, reclaimed by multiple generations as a pioneer and a survivor. On the surface, he was the exact same guy he’d always been. But inside he was a completely different man. And according to the press that accompanied his solo debut, Davis was the completely different sort of man who was interested in the history, politics and music of the Middle East. Which meant that “Black Labyrinth” necessarily included sitar, duduk, tablas and (double) violin. Which meant that I was more than a little reluctant to check it out. Which meant that — just as I’d done a quarter century earlier — I was steeling myself to dislike something I’d not yet heard.